The role of the Church in land acquisitions/land loss.

How did the Creek-Cherokee Lottery create the largest wealth gaps in America?

“In gratitude for his bringing them the gospel as a missionary of the Boston-based American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, early-nineteenth-century Cherokees gave Presbyterian missionary Samuel Austin Worcester the honorary Cherokee name “A-tse-nu-sti.” The name means “messenger.” Worcester’s message for posterity, echoing through annals from New England to Georgia to Oklahoma, remains a triple legacy for Indian-American relations, in missions, translation and printing, and the law.

The Worcesters worked from Brainerd, Tennessee, from 1825 to 1828, when they moved to New Echota, Georgia, capital of the Cherokee Nation, and where Samuel’s most lasting work began. He worked translating the Bible into Cherokee, using the Sequoyah’s (George Guess’s) newly developed syllabic alphabet. He assisted Elias Boudinot in publishing the Cherokee Phoenix, the first Indian newspaper in North America. He participated in public affairs with letters to officials and other publications. His opposition to removal of Cherokees west of the Mississippi River made him a conscientious objector to state law, as Georgia took Cherokee lands and dismantled Cherokee government in the face of inaction by the federal government and in defiance of the U.S. Supreme Court. Worcester’s incarceration with others who tested an 1830 Georgia law forbidding whites from entering Cherokee territory without state permission led to Samuel A. Worcester v. The State of Georgia in 1832. Cherokee leaders saw that case, in which the Supreme Court declared that Georgia laws could have no effect in Cherokee Territory, as a hopeful answer to the 1831 case Cherokee Nation v. The State of Georgia, in which Chief Justice John Marshall infamously found the Cherokees to be a “domestic dependent nation” with no rights a state was bound to follow.

The Worcester case, flouted by Georgia authorities and by Pres. Andrew Jackson, did nothing to stop the president and Congress from legislating forced removal of Cherokees and other Southeastern tribes. Despite being ignored in the 1830s, both cases influenced law and federal-Indian relations through the early twenty-first century.” (Source)

-

Background on the Plantation of Ulster and the granting of lands to Scotch settlers.

-

Inheritance customs and laws regarding land tenure in Ulster that carried over to America.

-

Waves of Scotch-Irish immigration to America in the 18th century, often via ports like Philadelphia.

-

Settlement of the backcountry and frontier areas from Pennsylvania to the Carolinas.1

-

How Scotch-Irish immigrants acquired land through grants, purchases from land speculators, or squatting.

- Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, March 18, 1831

“Cherokee Nation v. Georgia is an important case in Native American law because of its implications for tribal sovereignty and how to legally define the relationship between federally recognized Native American tribes and the U.S. government. In the late 1820s, the Georgia State Legislature passed two laws that declared Cherokee Nation tribal territory could be inspected, divided up, and distributed to white citizens in the state of Georgia. The laws also provided penalties and punishment to anyone who did not comply. Together, the laws were intended to force the tribe off its reservation lands.

The Cherokee Nation, under the leadership of Chief John Ross, sought to declare the laws unconstitu- tional based on treaties signed by the Cherokee Nation and the U.S. government. The tribe argued that the treaties provided for sovereignty and federal protection, and therefore the Cherokee Nation lands should be outside the state’s jurisdiction. The plaintiffs also argued that the Cherokee Nation constituted “a foreign state, not owing allegiance to the United States, nor to any State of this union, nor to any prince, potentate or State, other than their own.” This argument was intended to establish the Supreme Court’s jurisdiction in the case. Article III of the U.S. Constitution states that the Court has jurisdiction over cases “between a State or the citizens thereof, and foreign states, citizens, or subjects.” (Source)

-

Prevalence of intestate succession leading to heirs property issues over generations.2

-

Legal complexities with multiple heirs and fragmented ownership over time.

-

Economic impacts like inability to access credit or farm programs due to clouded titles.2

-

Heightened land loss risk, especially during economic downturns like the Great Depression.

-

After the Civil War, many formerly enslaved Freedmen acquired land, reaching over 16 million acres by 1910.1

-

But complex heirs property titles made this land vulnerable to forced court-ordered sales and partition sales.4

-

From 1910 to 2022, African American landholdings dropped by over 80% to just 4.7 million acres due in large part to heirs property issues.14

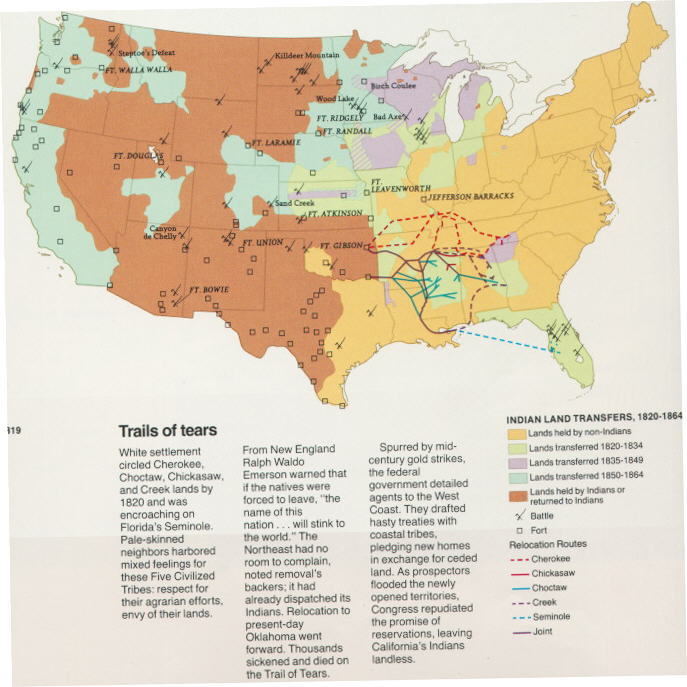

The 1831-1832 maps of the “Creek-Cherokee Indian Country“ details major rivers, towns, and important geographical features primarily located in what is now the state of Alabama, with some portions extending into Georgia and Florida, based on the historical distribution of the Creek Nation’s territory at that time. The maps were surveyed at the dawn of the Indian Removal Act, which forced the relocation of over 15,000 injuns, mostly Southeastern tribes, including the Miccosukee, Timucua, Seminole-Creek, from their ancestral lands to Indian Territory or I.T. (now the state of Oklahoma). To learn more, preview the Committee on Indian Affairs, January 4, 1831.

The next article provides an overview of Black Land Ownership in Georgia/ Heirs’ Property (aka Dead Capital and Fractional Lands)

1900-1921

Eatonton, Brier Rabbit – Forsyth

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, onecis et mollis.

Fitzgerald

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, onecis et mollis.

Alma, GA

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, onecis et mollis.